The Laffer ... Mesa?

A valuable new study on the Laffer Curve

The Laffer Curve, the most famous napkin sketch in economics, is simultaneously controversial and inarguable. The revenue-maximizing rate is clearly above 0% and below 100%, hence some curve must exist. But the curve’s policy significance is contingent on the inflection point: if revenue maximization is achieved at an all-in rate of 70% or more, as some believe, then the Laffer Curve has little relevance for contemporary tax policy debates. If it’s around 40%, as others have argued, then it’s clearly pertinent for public policy deliberations.

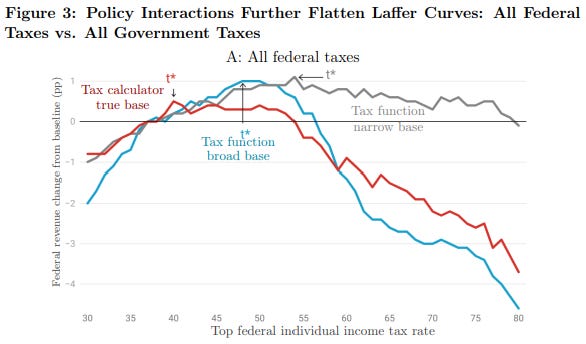

A new paper from Rachel Moore, Brandon Pecoraro, and David Splinter at the Joint Committee on Taxation provides compelling evidence that (1) the revenue-maximizing rate is much lower than many have believed and (2) Laffer Curves, in their words, “are flat”—that is, there’s a large range of top rates where further rate increases yield very little change in revenue collections.

The red line in the above chart is the one to pay attention to, and you can see that federal taxes raise about the same amount of revenue across a range of more than ten percentage points on the rate. The authors describe this by saying that the curve is flat along the top. I prefer to think of it as a mesa.

Unlike most prior research, which used simplifying rate assumptions (e.g., considering only labor income and ignoring lower rates on capital gains income, or disregarding taxes other than the federal income tax), the new JCT paper employs more realistic tax assumptions, yielding better-calibrated results. The JCT economists model the stylized tax bases used in previous analyses, some of which are too narrow and others too broad, while contributing their own “true base” (the red line in the above chart).

They find that overall federal tax revenues only increase by 0.5% when the top federal income tax rate increases from 37% to 40%, and that it plateaus after that before eventually yielding consistent revenue reductions on the other side of the curve.

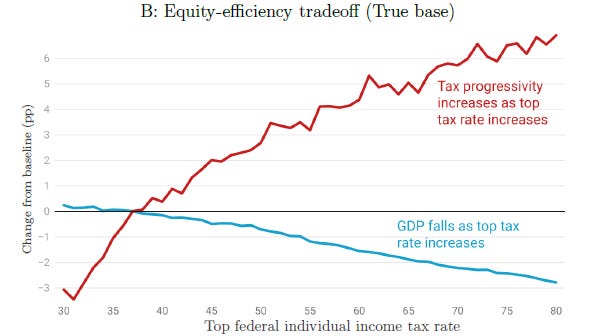

The authors identify an equity-efficiency trade-off in which GDP falls while tax progressivity increases, noting that over the flat region, “increasing the top rate raises relatively little revenue,” whereas “raising top rates primarily trades off between progressivity and growth.”

Don’t miss the significance of this combined with that flat region: across that region, higher marginal rates increase progressivity by reducing the after-tax income of high earners, not by increasing the income of low earners.

When higher rates yield higher revenues, governments can allocate some of that additional revenue to programs that benefit lower-income households. When raising top rates yields flat-lining revenue, the additional progressivity owes entirely to economic drag that reduces the income of those subject to the higher rates. The rich get less rich (and the economy gets smaller), but lower-income households don’t benefit. In fact, they stand to lose as well: lower economic growth is bad news across the income spectrum.

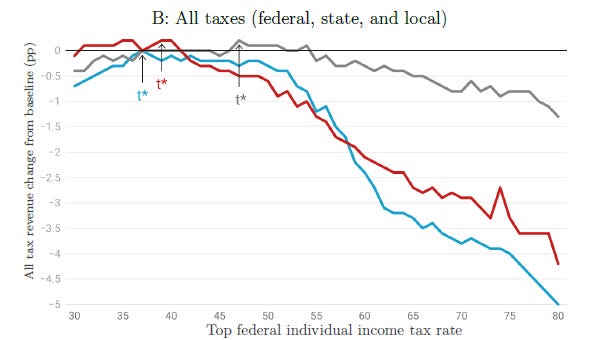

The JCT economists also calculate the revenue-maximizing top rate for the federal income tax when taking all taxes at all levels (federal, state, and local) into account, and find that we’re already on the mesa:

This suggests that there’s little aggregate revenue-raising potential of raising state or federal rates, though that doesn’t mean that state-level rates are themselves approaching the wrong side of the Laffer curve. Raising state rates can simultaneously shrink the pie but grow an individual state’s slice of that pie.

States that raise taxes should expect reductions on both the extensive (outmigration and capital flight) and intensive (reduced labor, investment, etc.) margins. This reduces the yield of those tax increases, and the JCT paper suggests that the systemwide effect may not involve much, if any, new revenue, but the tax-hiking state itself would still expect some level of revenue increase.

Of course, revenue maximization should not be the goal of tax policy in the first place. If 40% is the revenue-maximizing federal income tax rate, but a rate hike from 37% only yields extremely modest revenue gains while doing much more significant economic harm, that’s a strong argument against targeting revenue maximization even if you’d otherwise prefer the government to collect additional revenue. The slope of the curve before it goes flat is highly relevant here.

Moore, Pecoraro, and Splinter have substantially improved our understanding of revenue-maximizing tax rates. This paper has a lasting real-world impact.

Obligatory Marketing Note

My new consultancy provides tax policy research, writing, and other services, both project-specific and on retainer (or in visiting fellow-style roles). If you are in the market for tax policy research or know someone who is, please let me know.

Please Share this Substack

If you find this Substack valuable, please do me a favor and share it with colleagues and others who may be interested. And if you haven’t yet subscribed (it’s free), please consider doing so!