Understanding the R&E Expensing Timing Effect

The tax revenue impact of restoring immediate research and experimentation (R&E) deductions is mostly a timing effect. But what does that mean, exactly, and how significant is the effect? I explore that question in this issue of The SALT Road.

But first, please permit me a digression for a career update and a quick request.

With the dawn of 2026, my new business, Walczak Policy Consulting, is up and running. In addition to my continued association with the Tax Foundation, where I am now a Senior Fellow, I am working with the Platte Institute as a Senior Tax Policy Advisor and will be writing for the Mackinac Center as an Adjunct Scholar. I will be announcing additional affiliations soon, and publishing with other organizations on a project-specific basis.

My request: would you consider sharing my LinkedIn announcement with your network?

R&E Expensing Restoration Costs Are Mostly Timing Effects. But What Does That Mean?

Decisions about conformity to the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) are front-of-mind for many lawmakers as state legislatures reconvene for 2026. That’s understandable, but hesitation about restoring first-year research and experimentation (R&E) deductions is troubling. As I have written here and elsewhere, allowing an immediate deduction for research and development costs is sound tax policy—and, until very recently, there was near-universal agreement on this point. The federal government adopted the provision in 1954 and every state with a corporate income tax followed suit.

I won’t rehash the details of how a gimmicky reconciliation provision shifted the R&E deduction from first-year to five-year amortization in 2022, or how the OBBBA restores long-standing policy. You can read more about that in my prior coverage of the issue.

What I’d like to focus on: what it looks like for a state to transition back to first-year R&E expensing after shifting to amortization. I and others discussing the issue often note that, for states, amortization—and its reversal—is mainly a timing effect. But what exactly does that mean? My goal here is to demonstrate the timing effect with tables and charts.

When businesses are required to deduct their expenses over multiple years, they still get to deduct the full cost of that expense, but the delay comes at a cost in terms of inflation and the time value of money. Additionally, some businesses may have cash flow issues, particularly in their early years. They may have significant research expenses but not be profitable. More to the point, they may appear profitable—and be taxed as if they are profitable—if their revenues are counted in the current year, but the bulk of their R&E and other capital expenditures are shifted to later years. Amortizing R&E expenses can tax research-heavy firms at the wrong time, when they have limited ability to pay.

States, of course, generate additional revenue through amortization, since it erodes the present value of the deductions. But this additional revenue through inflation and other timing penalties is not particularly large, and states don’t need it. Lawmakers surely didn’t think they needed it between 1954 and 2021, when first-year expensing was permitted.

The problem is that now that states have shifted to amortization, restoring immediate expensing pulls more deductions into the 2025 tax year. We’ll walk through how this works, starting with this observation: the timing benefit of the shift to amortization was short-lived. All R&E is deducted eventually, so if a business can only deduct 20% of the cost in a given year, that may be a “savings” of 80% for the state in that year, but the other 80% of the deduction simply shows up as an obligation in future years.

Just like “buy now, pay later” schemes don’t actually reduce how much you pay, five-year amortization doesn’t reduce the size of the deduction states ultimately have to offer. And since new investments are made every year, it doesn’t take long until equilibrium is restored.

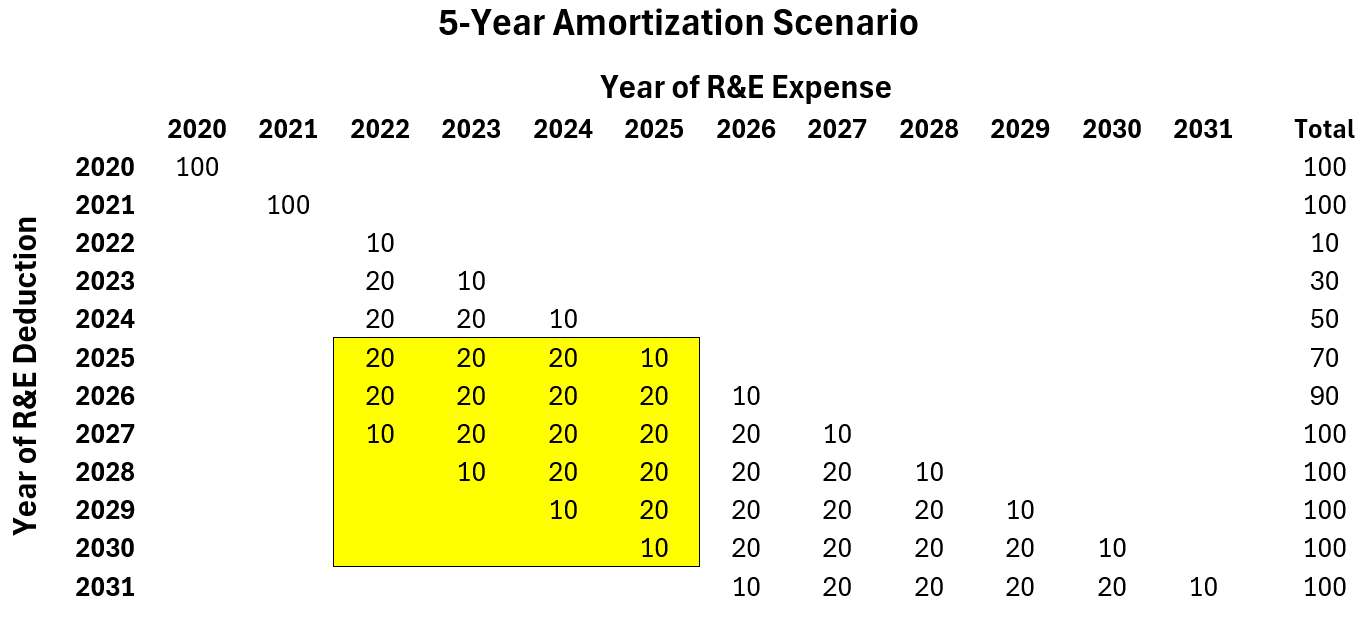

Imagine that every year, corporations invest 100 units in R&E. (The value doesn’t matter. That could be $100 million, $10 billion, whatever—we’ll keep this simple and just use consistent units.) Under first-year expensing, they’d collectively deduct 100 units from taxable income each year. Under five-year amortization, they spread it out—over six years, confusingly enough, due to a “split-year” convention where you actually deduct 10% in the first and last tax year.

It looks something like this. (We’ll get to the box in a minute.)

Note that in 2026, a state using amortization is offering deductions for investments made in 2022, 2023, 2024, 2025, and 2026. By next year, enough time will have passed since the implementation of 5-year amortization that, neglecting inflation and investment growth, states would be offering just as much in annual deductions as they were prior to amortization. All the savings were concentrated in a few years, as can be seen in the column on the right showing the total deduction value by year.

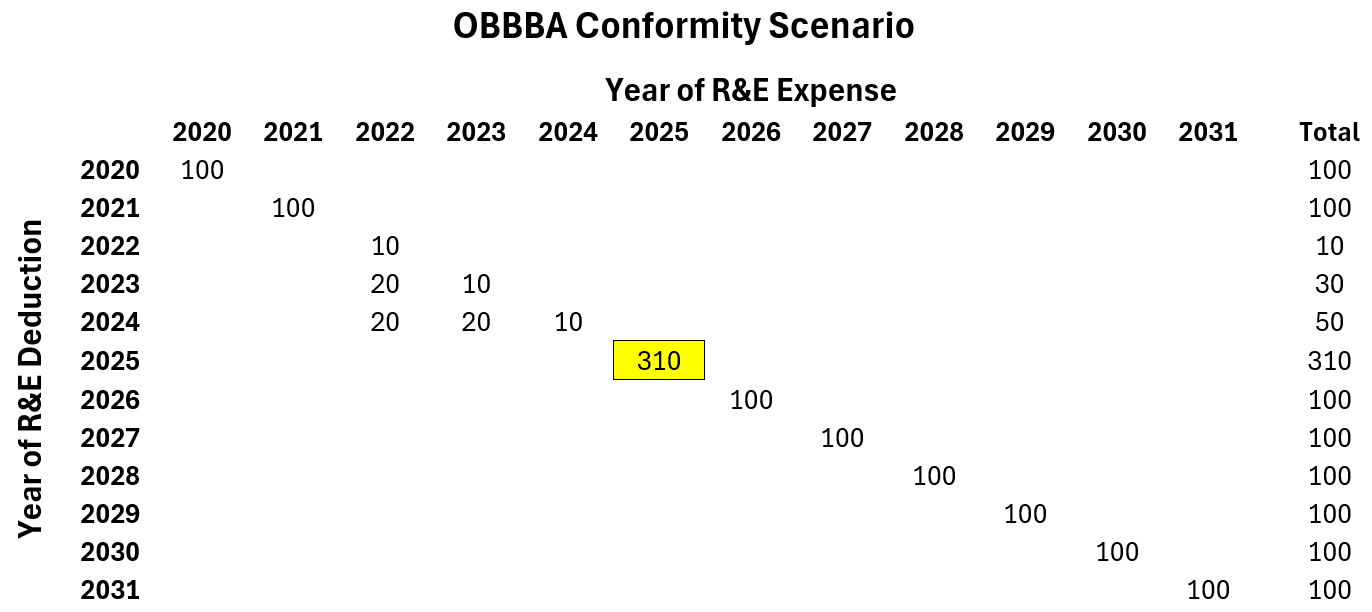

Now imagine a state follows the OBBBA in restoring first-year expensing. All recent expenses still being amortized can “catch up,” while all expenses made in 2025 and beyond are again deductible in full in the first year. That looks something like this:

You may have guessed that the units in the yellow box on the first table sum to 310, the deduction value for 2025 in this second table. This is a timing shift, though a dramatic one. All the deferred deductions from the past few years “catch up” in one year. Basically, states just unwind their prior policy, reversing their temporary windfall of recent years, but there’s certainly a short-term cost. (It’s important to note that corporate income taxes only account for about 2 percent of state revenue, and that R&E policy is a small slice of that small pie.) For tax year 2027 and onward, the annual deductions are the same as under amortization.

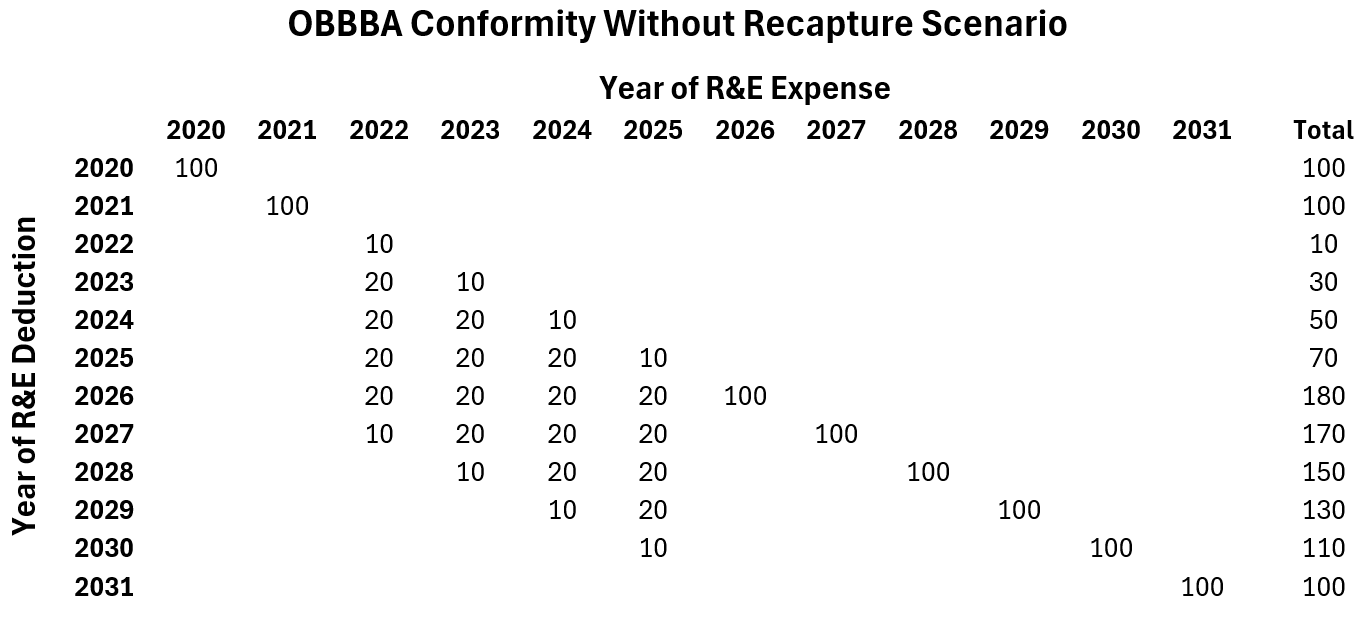

Delaware is the first state to choose a different option: requiring R&D investments already made under amortization to continue under that convention, but new investments obtain the benefit of first-year expensing. This isn’t entirely fair to prior investment, but it’s economically efficient inasmuch as retroactively restoring the deduction can’t change any of the investment decisions already made. (Congress had to deal with a different calculus: had it only restored the provision prospectively, companies may have delayed R&E investments in 2025, creating substantial economic disruption.)

The Delaware approach spreads out the “cost” of clawing back the state’s previous windfall over several years, making it more manageable for states with tight margins. That looks something like this:

Here’s what this looks like in cumulative deductions between 2020 and 2031. Assuming, for now, that firms make the same amount of R&E investment each year, there’s a convergence of both OBBBA conformity scenarios with pre-amortization policy. If, by contrast, states stick with 5-year amortization, every future year features the same amount of deductions (accumulated across multiple years), but the 2022-2026 shift is never fully “caught up.”

And here’s how that plays out year-by-year:

These are, of course, stylized examples. Research expenses aren’t identical from year-to-year. In fact, they’re growing, recently at a rate of about 5% per year. With consistent growth rates, the math doesn’t change much. With more variation, you get a bit more noise and a slight further shift in timing effects, but the basic story is the same.

States received an unexpected windfall when R&E deductions were postponed starting in 2022. There’s a cost to unwinding that policy. From one perspective, of course, it’s not a cost at all: it’s simply returning the windfall. But to the extent that this shows up now, states can choose to absorb the timing effect in one year or to follow Delaware’s model and spread out the reversal of the previous timing shift. What they shouldn’t do is hold so firmly to their one-time windfall that they permit their tax codes to penalize R&D in perpetuity.

Obligatory Marketing Note

My new consultancy provides tax policy research, writing, and other services, both project-specific and on retainer (or in visiting fellow-style roles). If you are in the market for tax policy research or know someone who is, please let me know.

Please Share this Substack

If you find this Substack valuable, please do me a favor and share it with colleagues and others who may be interested. And if you haven’t yet subscribed (it’s free), please consider doing so!